Cities are never static. They are restless organisms, thickening, eroding, expanding, and remaking themselves. Sometimes quietly — like a tree widening at its core. Sometimes dramatically — like a skyline rising or a coastline shifting. But in every case, cities are engaged in the same act: the continual rewriting of their own geography.

Few processes make this more tangible than land reclamation — the creation of new ground where there was once water. It is a strange inversion of natural order: humans dragging earth into the sea, reshaping topography as though editing a manuscript. And often, the raw material of this expansion is not pristine soil, but rubble and residue — the cast-offs of earlier ambitions. Cities, in this sense, are palimpsests, layering futures over the debris of their pasts.

Consider New York. One of the city’s most hidden legacies lies beneath the East River. Rubble from bombed-out London, carried back across the Atlantic in ballast ships after the Second World War, was poured into the shoreline. That ruin now supports the FDR Drive and the East River Esplanade. To run along that edge is, unknowingly, to trace the ghosted streets of another city. The trauma of London’s destruction became the foundation for Manhattan’s expansion.

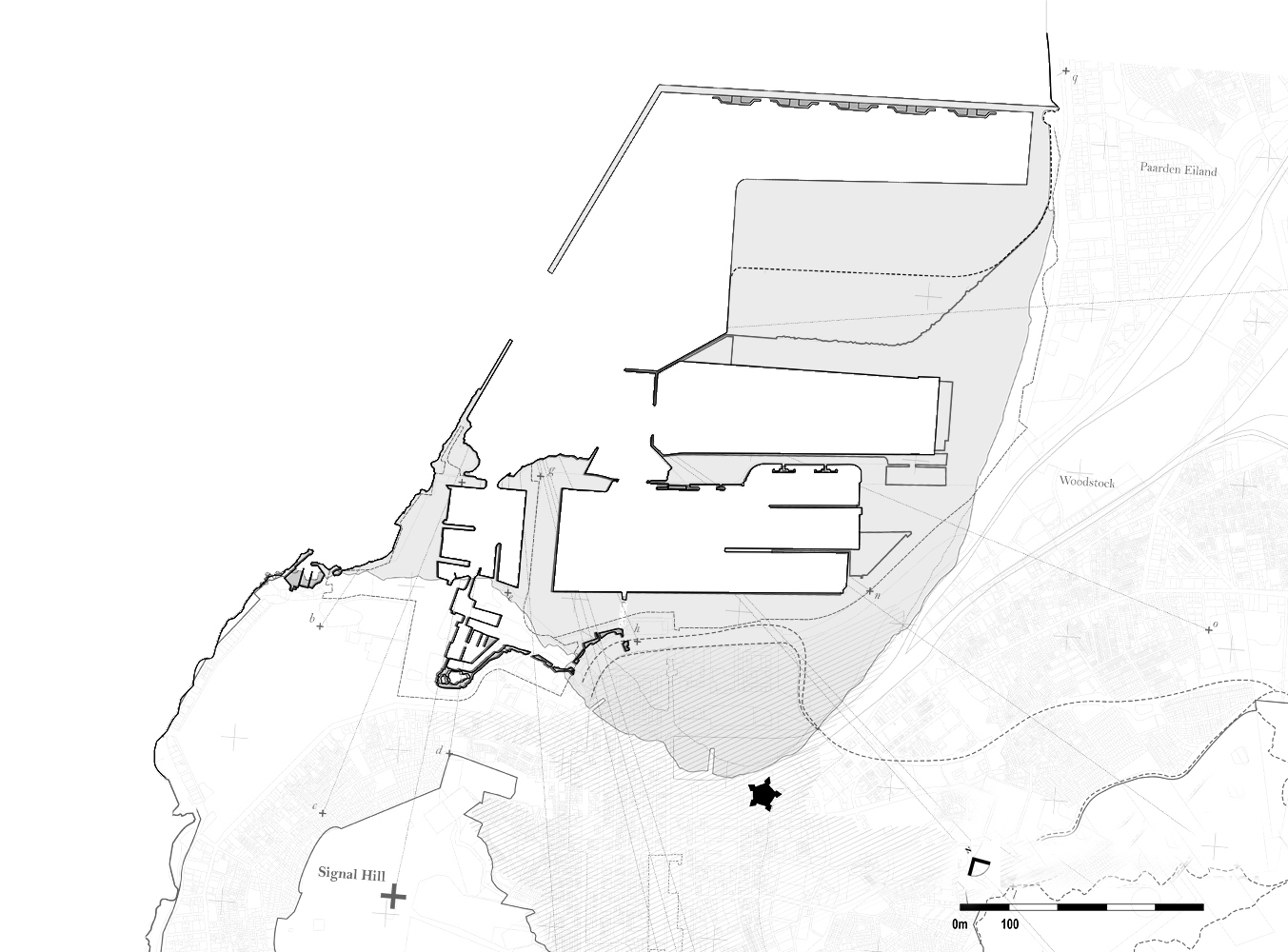

Cape Town offers another lesson. In the mid-20th century, Table Bay was dredged and drained. To fill the void, stone was mined from the flanks of Table Mountain. The mountain itself was dismantled, crushed, and packed into the ocean to extend the foreshore. The city literally amputated its geography to project itself outward — a gesture as ambitious as it was irreversible. Highways, administrative complexes, and speculative office towers rose on land that had once been sea, tethered by rock that had once loomed above.

Elsewhere, reclamation becomes spectacle. Dubai has transformed this act into a global performance. The Palm Jumeirah, The World Islands, and more recent projects are feats of engineering that treat land-making not just as utility but as symbol. These islands are shaped to be seen from satellites, promotional material for an ambitious future where the sea itself becomes real estate. Sand is pumped, sculpted, and fixed into formations that are both fragile and monumental — an audacious overlay of capital onto coastline.

What distinguishes Dubai is not the scale of its reclamation, but its intent. Whereas New York or Cape Town expanded from pressure — the need for space, infrastructure, or administration — Dubai expands as projection, broadcasting itself on the world stage. Its reclaimed land is less about survival than about spectacle, a geography built to attract investment, tourism, and prestige. Yet beneath the dazzle lies the same logic: the city asserting control over nature, refusing to accept its limits, rearranging the earth to sustain its own momentum.

Even Venice and the Netherlands remind us that reclamation is not only an act of ambition, but also one of survival. Venice’s fragile existence depends on dredging and reinforcement; the Dutch have spent centuries curating their landscapes through dikes and polder systems, claiming soil from the sea with a precision that is both elegant and existential. Here, reclamation is not a choice but a necessity.

Taken together, these stories reveal a deeper truth: architecture and planning do not only shape cities from above. They also depend on the subterranean movements of matter itself — rubble, sand, spoil, and stone as much as steel and concrete. Every street has a hidden geology. Every tower rests on buried histories.

At Pemba, we see these narratives as more than curiosities. They are reminders that architecture is not only about form but about ground: about what is inherited, what is erased, and what is constructed. In an age of rising seas and climate uncertainty, reclamation is not only a story of expansion but a pressing question of resilience. How will tomorrow’s cities negotiate the edge between land and water? What new identities will be written, and at what cost?

We see these questions not as abstractions but as opportunities for design — to work with land responsibly, to think generationally, and to recognise that every foundation is also a future memory.